The Slate Series

A Folio exploring the Welsh Slate industry

and its symbiotic connection with this unique landscape

The Slate Series.

Snowdonia has always been a source of inspiration, ever since my first experiences walking the mountains as a boy. The incredible shaping of the landscape by the once proud Slate industry has only added a source of fascination. The relationship between the often remote, hard landscape and the riches sought within it defined the culture of a region, which in turn re-defined and re-shaped the landscape in often dramatic ways. It is hard to imagine the scale of human endeavour, made all the more astounding by the extreme environmental conditions that had to be endured. When walking around the remains of these places, it is just possible to get a glimpse of how it must have felt.

Through The Slate Series I explore the connection of the industry to the landscape. This is not meant to be a detailed factual account of the workings of slate mines, but to set them within an environmental context, exploring the scale and extremes of the many workings and the landscape that surrounds them with the hope of trying to invoke a flicker of emotional connection to the past.

This portfolio is an ongoing body of work, that I will continue to expand on over time.

The Llanberis Pass from Dinorwig.

Rhosydd

Rhosydd was my inspiration for this series. The 2 mile miners track through Cwmorthin quarry, winding past Llyn Cwmorthin and up a steep gradient has a unique eerie feel even in the most pleasant weather conditions.

The site itself is nestled on the approaching slopes of Moelwyn Mawr and numerous remains still exist. Rhosydd was one of the more remote workings, and the working conditions were reputed to be amongst the worst. The Slate was won largely underground, although West Twl, the first major working, was an open pit.

The first quarrying began in the 1830’s, with mixed fortunes and finally closed in 1930. The surrounding landscape is especially wild, adding to the sense of isolation that makes it hard to imagine the once thriving industry that took place.

Dinorwig

The impact of the Dinorwig workings carved into the mountainside never lessens regardless of how many times I see it. The great tiered galleries carved into the mountain side make a formidable approach out of the Llanberis Pass.

I will never forget my first foray, walking from Dinorwig village. Venturing out onto one of the many tips, I felt slightly uneasy at the height as it jutted out above the valley floor below; only to turn around in wonder at the countless further galleries above me, cut like a giant’s staircase into the rock.

A palpable sense of the physicality of the work that employed 3000 men, working in rain, ice and snow at heights up to 1500 feet above sea level is ever present.

Dyffryn Nantlle

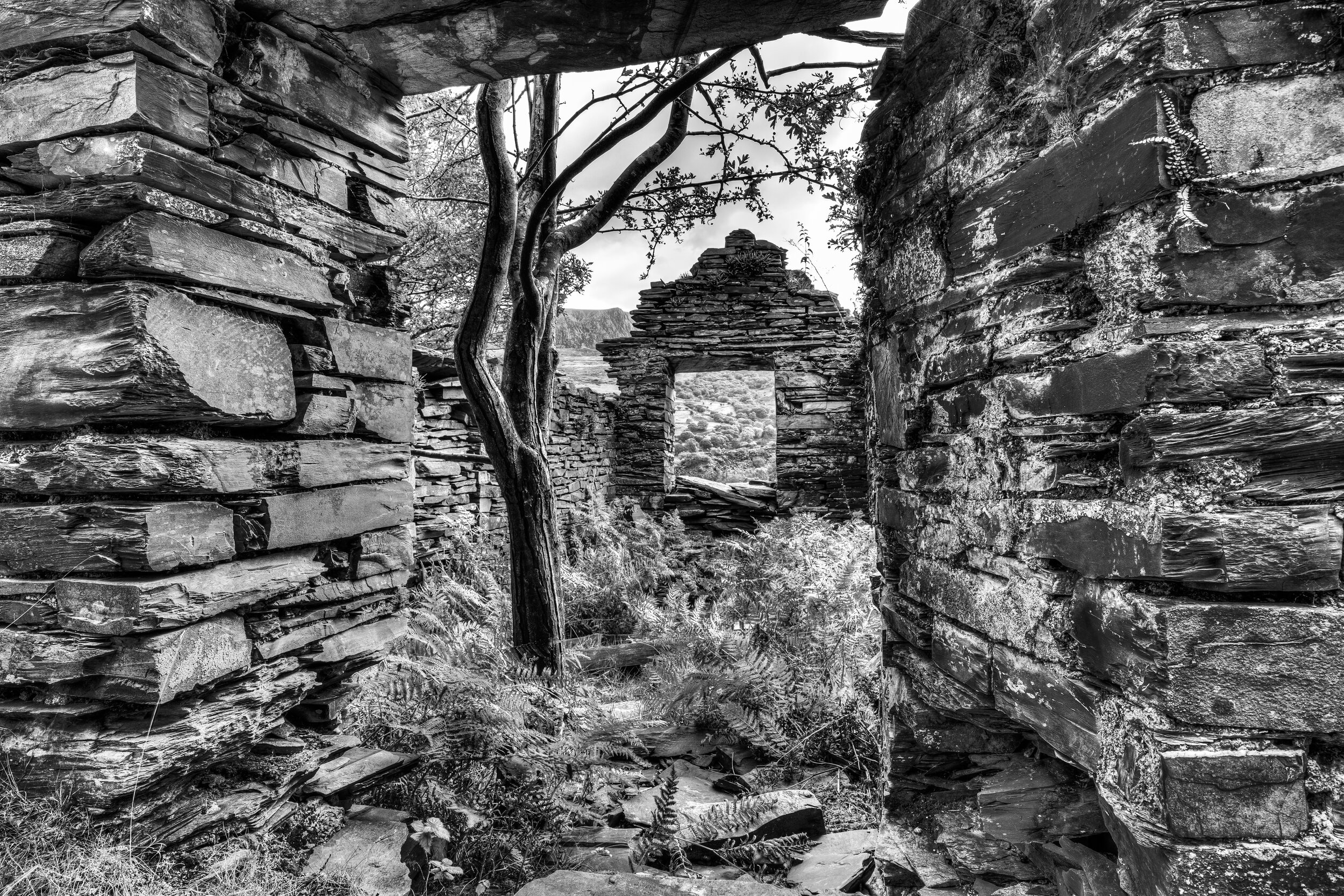

Standing in the grounds of what was once Plas Dorothea is an unnerving, uncomfortable experience. The Landscape has truly reclaimed the grounds of Dorothea, the largest of the quarries in the Nantlle Valley. Gnarled trees wind their way through roofs and Ivy crawls through windows, creating skeletal like structures fused around the abandoned ruins.

Dorothea, and the smaller workings that surround it were examples of the huge open pit quarries known as twls. The pumps that kept them dry have long since been silenced allowing nature to creating still, silent lakes of water. There is a long history of slate in the Nantlle valley, with Cilgwyn quarry dating back to the 14th Century and quarrying continues to this day at Pen-yr-Orsedd high above the original twls.

The Rhiw Bach Tramway

The gently twisting Rhiw Bach Tramway traverses some of the most stunning scenery you will likely find in North Wales. From Rhiw Bach quarry, it passes through bleak, marshy moorland, past Blaen-y-Cwm & Cwt-y-Bugail, before winding around Llyn Bowydd and ending with stunning views across to the Molewyn mountain range in the south west and Moel Siabod to the north west. This is the Welsh wilderness at its best! The tramway was built to connect a series of workings to the Ffestiniog Railway’s Diffwys Station. These were much smaller workings than their bigger cousins in Blaenau Ffestiniog, and often struggled to remain viable in difficult times. Never-the-less, walking around these places its clear they each have their own character and story to tell.

Cwt-y-Bugail, looking towards Rhiw Bach